News and blogs

205 articles

Blog

BlogMichael Holland sets the analogue to digital vision

Our chief executive Michael Holland recently presented an opening talk at the annual Cavendish Square Group Conference

News

NewsSupporting children’s mental health through art

Our creative art therapy service is an accessible and inclusive form of therapy, which uses creative expression as a tool for understanding emotional growth.

News

NewsStrengthening community CAMHS across North Central London: A new collaborative approach

We’re pleased to share an important update about the future of Community Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS)

News

NewsTavistock Centre library summer closure

We’re closing our spaces to make big improvements ready for the new academic year

News

NewsReceive appointment reminders via our patient portal

Patients at our gender identity clinic (GIC) can now receive appointment notifications and reminders through our patient portal.

News

NewsStudent uses manga art to express emotions in their studies

A student has been using manga art to help express emotions from their studies and therapy sessions.

News

NewsSupporting parents and children through our family drug and alcohol court (FDAC) service

Our family drug and alcohol court (FDAC) service hosted a showcase event

Blog

BlogRelational practice in our Camden adolescent intensive support service

Maintaining a safe and robust crisis service through ‘Relational Practice’ in an Adolescent Intensive Outreach Support Service

News

NewsTavistock and Portman student receives Royal College of Nursing Foundation award

Student recognised in the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) Foundation Impact Awards.

News

NewsGloucester House introduces pet therapy

Gloucester House, our Trust-run school, has been working with the national charity Pets as Therapy (PAT) to enhance the health and wellbeing of their students.

News

NewsTavistock Consulting at 30: Videos of celebratory event

Recordings from an event celebrating 30 years of consultancy practice.

News

NewsTavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust merger update

Update on Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust merger plans.

News

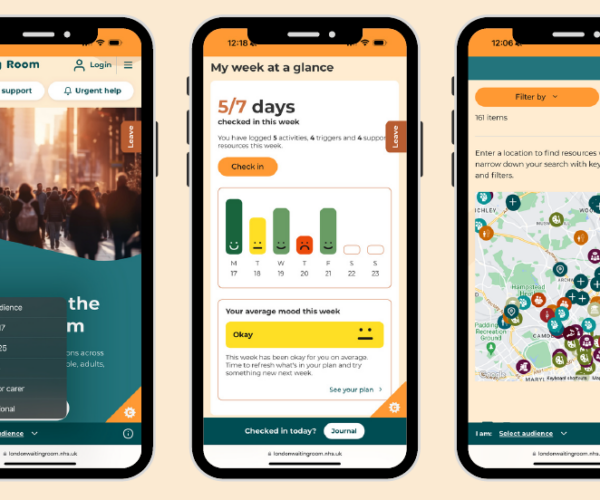

NewsWaiting Room relaunches with new features and support options

Showcasing a variety of health and wellbeing services for people of all ages across London.

News

NewsWaiting Room shortlisted for HSJ Digital Awards

Our Waiting Room has been shortlisted in the ‘Improving Mental Health through Digital’ category.

News

NewsCelebrating 30 years of Tavistock Consulting

Tavistock Consulting is our specialist organisational development and change consultancy

News

NewsNotice of Council of Governors elections 2025

Notice is hereby given that elections will be held for the Council of Governors for The Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust.

News

NewsSupporting autistic children at risk of harming others: Conference February 2025

We welcomed an array of professionals from across the UK to our FCAMHS Conference on Thursday 13 February.

News

NewsCelebrating Mental Health Nurses Day

Mental Health Nurses Day encourages us to celebrate the incredible work of mental health nurses.

News

NewsFebruary 2025 open day

We were delighted to welcome aspiring postgraduate students to our on-site open day on Saturday 1 February 2025.

News

NewsThree tips to help children express emotions

Adi Steiner shares guidance on how to facilitate conversions about difficult things with children and young people

News

News2024 publishing successes

Browse some of the articles, chapters and books published by our staff, students and alumni over the past twelve months.

News

NewsCamden mental health support team for schools showcased in NHS England Medical Director visit

Dr Adrian James visited our Camden mental health support team.

News

NewsSupporting Camden foster carers through a monthly support group

How our Growing with you CAMHS service supports foster carers.

News

NewsReady to kickstart a new career in 2025?

Join our in-person open day on Saturday 1 February 2025 to get a real taste of student life at The Tavistock and Portman.