Art at the Tavistock and Portman

Wander around the hallways of the Tavistock Centre and you will see works of art hanging along every corridor and bold stabs of colour in our public spaces.

Art plays an important role to the life of our Trust, and we are always looking to find new ways to engage our staff, our patients and everyone connected with our work.

Our art collection

Our collection differs from those possessed by the great London hospitals and Institutions founded centuries ago, in that all of our works are modern. The oldest pieces date back only as far as the 1960s.

Since 1990, when the collection began, most of the works have been lent by artists, many of whom are local to the Centre’s North London site. Some have been willing to let us hang some of their most engaging paintings, for example Jamie Boyd’s mysterious Mediterranean landscapes. Perhaps some of these were offered because they are too large for private homes or even for galleries; some in gratitude because the artist or their families had been helped by us; and some because they supported vigorously the principle of good art in public buildings. One particularly rich haul of first-class work was made possible by the Connaught Brown Gallery’s willingness to open up its warehouse, where many remarkable works were stored – thus works by Paul Richards and William MacIlraith are on display. Many of Florence Spencer’s outstanding paintings (for example The Red Queen) were stacked in a large cupboard in her flat before they were unearthed by our sharp-eyed founder-curator Caroline Garland.

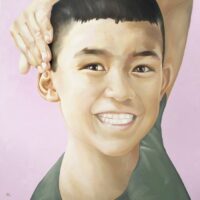

Amongst the many works worth visiting are Malcolm Ross-White’s startling and witty Big Man; Amanda Welch’s thoughtful and introspective canvases; Annabel Obholzer’s imaginative representations of mythical encounters; Lucinda Oestreicher’s cleanly painted abstractions; and among the younger, newer artists, Austen O’Hanlon, whose paintings offer a dream-like version of ordinary encounters with passers-by. Jamie Boyd’s magical-realist Lion in the Bath pleases many of the children, not to mention the adults, who pass by it every week.

We have born this in mind throughout in selecting the works we have chosen to hang. We invite you to come and view them and to think about them with us.

Related services

-

Creative art therapy

Art therapy supports children and young people’s emotional wellbeing and improved engagement in school.

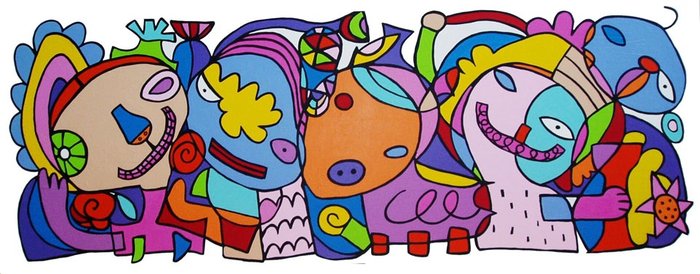

The banner at the top of this page is a crop from a piece commissioned from Dugald Ferguson for our refurbished seminar rooms.

Recent art news

-

News

NewsEtaoin Shrdlu: Trust showcases unique exhibition on vanished civilisation

Last month, we hosted a new art exhibition at the Tavistock Centre titled Etaoin Shrdlu by Richard Frost.

-

News

News‘We’re on each other’s team’: first exhibition of 2024 at the Tavistock and Portman

The Tavistock and Portman is starting 2024 with an imaginative exhibition of collages, from artist Gareth Schweitzer.

-

News

NewsFrancesca Apicella art exhibit at the Tavistock Centre

The vintage-inspired artworks explore the artist’s personal struggles with chronic illness through strong female icons.