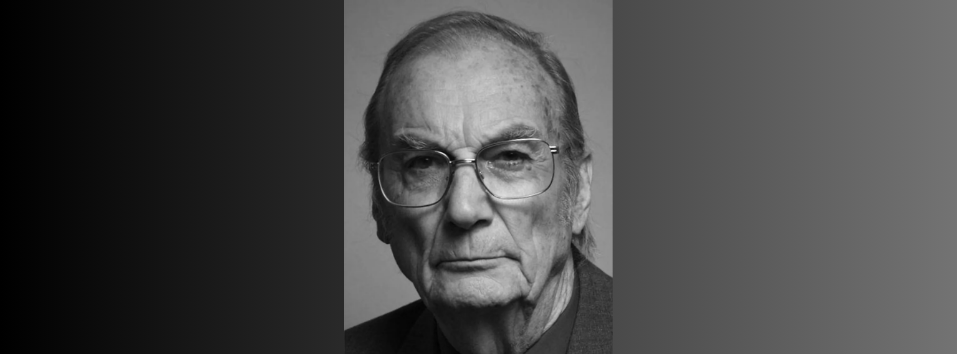

Remembering Dr Colin Murray Parkes (1928 – 2024)

Throughout its history the Tavistock and Portman has influenced not only mental health practice, but also society more widely. Sometimes this has been on the back of our groundbreaking research and approaches to mental health and sometimes, as with Colin Murray Parkes, it is simply down to the words we use. Maybe it is our emphasis on talking therapies that makes our clinicians able to use language in a way that unlocks emotions and inspires. Myooran Canagaratnam, Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist, reflects on the unexpected influence of Colin Murray Parkes who died a year ago.

In January 2024, I heard that Colin Murray Parkes, a psychiatrist and leading expert on grief and bereavement support, had died at the age of 95. Dr Murray Parkes had worked at the Tavistock with John Bowlby, who developed Attachment Theory, and went on to play an important role in supporting those affected by disasters such as Aberfan, 9/11 and the 2005 Tsunami in the Indian Ocean. It was Murray Parkes who originally used the phrase “Grief is the price we pay for love”, in his 1972 book Bereavement: Studies of Grief in Adult Life. The words were later uttered in a speech by the late Queen Elizabeth II following the September 11 attacks, prompting US President Bill Clinton to tell Alistair Campbell (Prime Minister Tony Blair’s Communications Director) to find whoever wrote the lines and hire them.

I had little previous awareness of Dr Murray Parkes’ work, but after reading his obituary, I listened to a talk he had given on insecurity and extremism, broadcast on Radio 4. I was struck by the connections to both the Tavistock’s past and the world today – firstly how he had taken Bowlby’s ideas on parent child relationships and applied them to relationships at the level of groups, societies and countries. And secondly how relevant his talk was to the conflict riven and polarised times we are all living in.

It moved me to visit the Tavistock library and seek out the book Responses to Terrorism, which Dr Murray Parkes edited and contributed several chapters to. In it he describes the attachments we can form to people, leaders, ideologies, nations and religions – and how these different attachments can overlap and conflate. He formulates the unremitting cycles of violence seen in many international conflicts in terms of problems related to these attachments. Attachments which become ever stronger when under threat. He elaborates a model of how responses to terrorism can feed cycles of violence. It includes the perception of the violent act, the early response, role of legitimising authorities and polarising inflammatory strategies. Insecurity, fear and hypervigilance to threats play key roles at each stage, enhancing the likelihood of destructive escalation.

The corollary is that interventions which increase psychological security can promote change at each point, which can help break the cycle. Drawing from his experience of bereavement work, Dr Murray Parkes identifies the importance of acceptance of help from wise leaders from the outside who show patience respect and care for both sides of a conflict, listening and striving to understand their perspectives. He is clear that to understand and empathise is not to agree, take sides or condone. But it is only such understanding that can provide the conditions for old beliefs and assumptions to be reevaluated and new ones formed.

These ideas are very familiar of course to clinicians working therapeutically in a range of disciplinary perspectives. Their reach reminds us of the contribution the Tavistock and Portman has historically made at the level of policy and society, and will continue to make as we pioneer innovative education and research and use talking and relational therapies to make a meaningful difference to people’s lives. To quote Colin Murray Parkes, when faced with the loss of people and things to which we are attached, we need time to change our assumptions… “not by forgetting the past but by remembering it, and building on it a more secure and hopeful future.”

It is perhaps reassuring to find that the words of such an eminent and influential thinker from our past connect so readily with the Trust’s values of excellence, inclusivity, compassion and respect. His words resonate and give an indication of how we apply these values through our work, holding emotions with compassion and creating a space for thought.